In any public setting, or perhaps even within the walls of your own office, odds are there’s at least one person in your line of sight who is microdosing psilocybin or LSD, and likely several others who are contemplating the same. The idea of doping at work would have been grounds for dismissal as little as a few years ago. But these days, especially in the tech sector, therapeutic psychedelics are considered as ordinary as visiting the chiropractor.

Psychedelic drugs and their medicinal benefits have seen a huge shift in popularity of late. Gone are the days of “magic mushrooms” and acid being the party drug of choice for ravers, or the things that the CIA dabbled in on Project MK-Ultra. They are the topic of countless Netflix documentaries, research studies, GOOP newsletters, and more. It can feel like everyone is microdosing something these days.

Over the last seven years, Google search traffic for the term “microdosing” has increased tenfold, as has the number of clinics across Canada and the US specializing in psychedelic-assisted therapies. It can be argued that the data on efficacy of these treatments is muddy, depending on whose research you’re looking at, but the data only tells part of the story. A portion of psilocybin microdosing studies point to a potential expectation and “placebo effect,” however. A more recent paper by Dr. Vince Polito of Macquarie University in Australia dives into the data from studies compiled between 1955 and 2021, and sufficiently debunks the placebo theory. Microdosing psychedelics does have a clear impact on mood and broader mental health.

“Being isolated at home with nothing to do, society as a whole actually had time — for the first time in recent history — to step back and look at their own wellbeing as more than just physical health.”

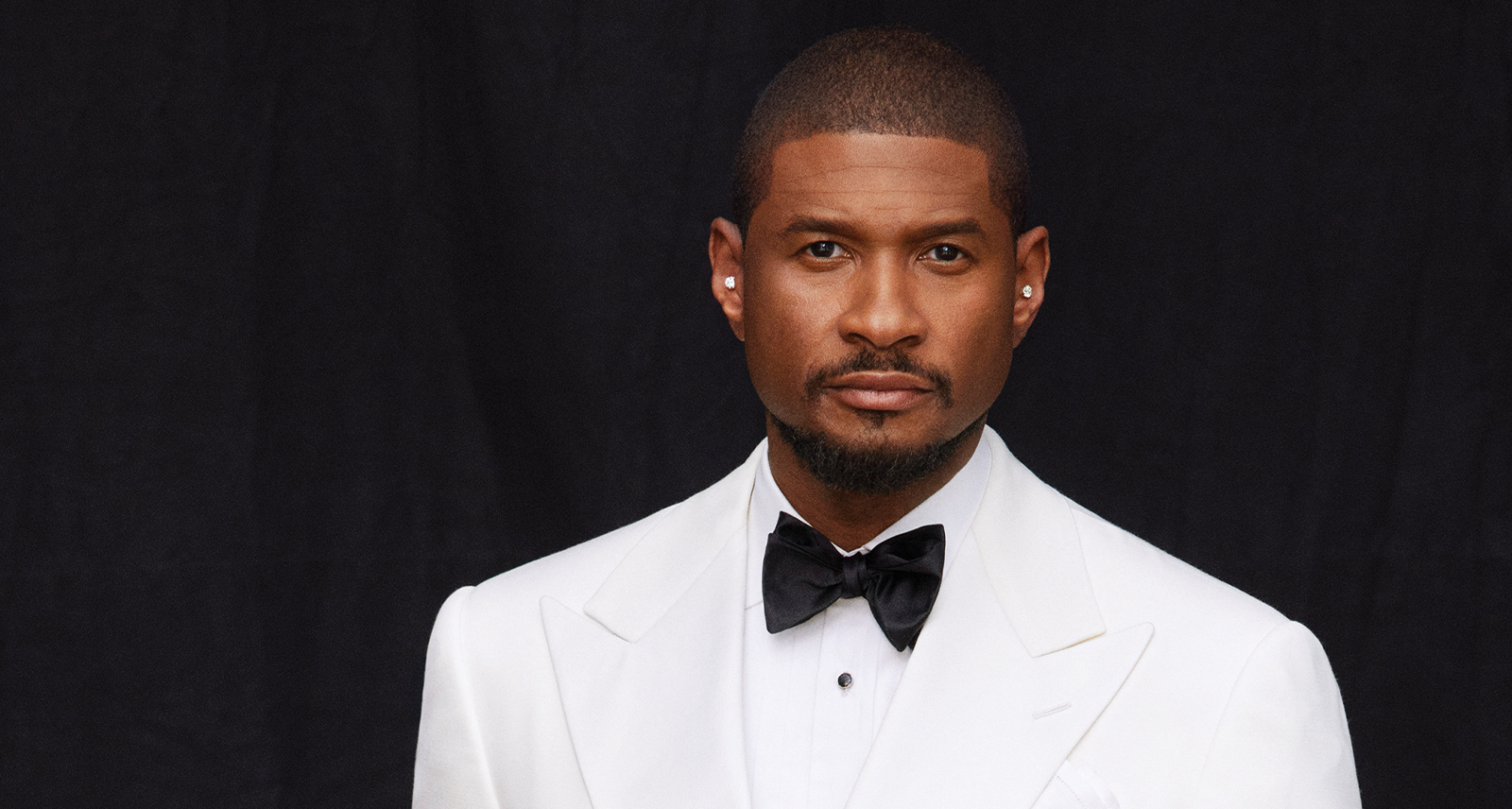

Payton Nyquvest, founder and CEO of Numinus.

For the sake of clarity: a microdose is roughly a tenth of the so-called recreational dose of the substance in question. The intent is to get just enough of the substance into your system for its baser effects to influence your mind and body, without hallucination, inebriation, or compromising the ability to function.

I have no shame in admitting that I too have jumped on the microdosing bandwagon recently. With lofty promises of increased focus and creativity, paired with reduced anxiety, microdosing psilocybin reads as any writer or editor’s “miracle cure” when pressing deadlines and mountains of assignments pile up. While I’m not shouting its praises from rooftops — and wouldn’t go so far as to say that my existence has been granted new meaning — I can at least attest to what the fuss is about.

That same promise of a “silver bullet” has surfaced with both ketamine and MDMA when looking at treatments for depression and PTSD. Once known primarily as a veterinary tranquilizer turned party drug, ketamine trials for depression rapidly showed promise of turning things around in cases where conventional drugs and therapies fell flat. When dosed alongside therapy with clinical psychologists, a significant number of patients started seeing light at the end of the tunnel that no other treatment could provide.

Meanwhile, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is finally on the cusp of full FDA approval of MDMA — ecstasy, in essence — for the treatment of PTSD. First founded stateside back in the late ’80s, the long-term results of MAPS’ decades of research into the uses of MDMA hold the greatest promise. In its phase three trials, 88 per cent of patients experienced a clinically significant reduction in PTSD diagnostic scores two months after their third session of MDMA-assisted therapy. In addition, 67 per cent of patients no longer met the clinical threshold for PTSD diagnosis.

But how did we get here? How did we transition from fear-mongering about drug use and the infamous War On Drugs to executives, financiers, tech gurus, and editors having open conversations about psychedelics as if they were coffee or a new craft beer? According to Payton Nyquvest, founder and CEO of Numinus, one of Canada’s leading integrated mental health care providers specializing in psychedelic- assisted therapies, the global COVID pandemic played a major part in getting these therapies in front of a broader audience. “Being isolated at home with nothing to do, society as a whole actually had time — for the first time in recent history — to step back and look at their own wellbeing as more than just physical health.”

While it’s true that the pandemic brought the world of microdosing into broader society, from an origin story standpoint, we need to dig a little further. James Fadiman’s 2011 book, The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide was one of the first pieces of modern lit to dive into the topic of microdosing, and within a few years, word of the book and its proclamations on the benefits of microdosing psychedelics had made the rounds of Silicon Valley. The 2015 Rolling Stone article How LSD Microdosing Became the Hot New Business Trip revealed how microdosing LSD had become commonplace amongst San Francisco tech startups. As with any good story hook, a wave of content followed, leaving plenty for the curious to sleuth through by time the pandemic rolled around.

The legalization of cannabis also played a part in the societal shift towards accepting psychedelics. Canada moved from a time where police could bust you for smoking a joint on a street corner, to recreational dispensaries getting “essential service” status during the pandemic so quickly, and for the majority cannabis became inconsequential. Though their effects differ, psilocybin mushrooms have slowly slid into the same bracket of harmlessness, perhaps on account of also being naturally occurring, and are right in the thick of their own transitional phase of acceptance.

At time of printing, Toronto has no fewer than ten mushroom dispensaries — each of varying degrees of sketchiness — selling dried mushrooms, mushroom-based edibles, and measured microdosing capsules at a cash-only counter. Given the still-illicit nature of the drug, which is still wholly illegal in recreational form, these dispensaries are frequently raided by the police. Much like the days of not-so-legal cannabis dispensaries, visitors are asked to identify their prevailing “ailment” before completing any purchase. Considering the current state of Canada’s health care system, especially when it comes to mental health resources, this trending form of self-help is providing Canadians with an alternative therapy path when conventional routes remain heavily backlogged. Gaining access to a clinical psychologist for anxiety, depression, ADHD, and other disorders can take in excess of a year, depending on what part of the country you’re in. This leaves only a handful of paths: trust that your family doctor is knowledgeable enough to trial you on a prescription, seek out paid practitioners in private clinics, or venture down the path of self-medicating.

Those last two words might give us pause. But remember CBD? The doesn’t-get-you-high cannabis component that has taken over all sorts of pain management practices started off as part of prescribed pain management but has since been made available for all to dabble with as they see fit? From stay-at-home parents to bankers to construction workers, a huge swath of the population is “self-medicating” with CBD already. While we needn’t view every illegal substance through that lens, there’s a clear and defined path as to how perception has shifted.

Between psychedelic-assisted therapy clinics like Numinus and the significant influx of capital into the medical psychedelics category in general — in 2017 somewhere north of two billion dollars had been invested in research and studies — it’s safe to say that microdosing and the use of ex-party drugs in medical treatment is no passing fad. It’s almost funny, when you think about it. After decades of Puritans calling cannabis a gateway drug, it turns out they were kind of right.